Collector’s Guides • 02 Oct 2019

The Patek Philippe Grand Complications

It is without a doubt that, as excellent as Patek Philippe is throughout their wonderfully diverse collections, it is with the Grand Complications, as seemingly esoteric as they may be – especially at the very top end – therein lies their métier. Whether it is a perpetual calendar chronograph, which is among their most archetypal works of art, or a rattrapante, or a minute repeater, one can be assured that the acquisition of a Grand Complication is an induction into the very best watchmaking yet conceived; an acquaintance with the complex, the fascinating, the pursuit of exceptionalism. It is the type of watch that is typically shrouded by a shirt cuff, eliciting a discreet nod of approval from a fellow collector when it makes an emergence – that is the quintessential Patek Philippe patron.

Perpetual Calendars

Patek Philippe’s history of perpetual calendar wristwatches begins in 1941, in the throes of the Second World War, with two watches: the now-famous 1518 perpetual calendar with chronograph, and the 1526 perpetual calendar. Hardly an auspicious year to launch a complicated watch, let alone two – demand for timekeepers were largely restricted to time-only aviator’s watches – Patek, like the other great Genevan watchmaker, Rolex – demonstrated great derring-do in the face of political and economic turmoil and brought to the world two groundbreaking watches which, for the next seven decades, established this august maison as the best watchmaker in the world.

Both the refs. 1526 and 1518, as progenitors, established aesthetic and technical blueprints for all future Patek Philippe perpetual calendars that would come after – and some argue, even for those of other makes. It was more than five decades before another perpetual calendar chronograph was introduced after the 1518. Featuring a double-window layout at twelve, displaying the day and month, and a large subdial at six o’clock, circumferentially indicating the date and housing the moonphase display and running seconds, this template is seen today in the 5320 perpetual calendar, as well as in the perpetual calendar chronograph and rattrapante respectively, the 5270 and 5204.

In 1993, the year Philippe Stern became president (and the year I was born), Patek Philippe launched the ref. 5050, its first perpetual calendar wristwatch to be fitted with a retrograde date function. It was succeeded in 1998 by the 5059, a very elegant, regal reference, one of my favourite Patek watches of the ’90’s.

The 5059 offered a case that was considerably more complex, angular, that that of the lithe 5050; cabochon-capped lugs and an Officer’s-style caseback added to the Roman numerals and apertures at the extreme 3’ and 9’ o’clock positions, cut out of its porcelain dial, add to its intrigue.

The 5159, launched in 2007 with an increased case diameter of 38mm, offered the same case details as its immediate predecessor but also featured a hand-guillochéd centre, emanating radially from the centre of the dial. Offering the same retrograde feature but housed in a more streamlined, Calatrava-esque case is the 5496, currently available in rose gold and platinum.

Another iteration in the means by which Patek laid out information in its perpetual calendars came with the ref. 3940, which replaced the iconic 3450 and its classic Patek aesthetic, on which the 5320 of today is arguably modelled. Rather than utilising apertures, the 3940 utilised three subdials, at three, six, and nine – three for the leap-year cycle; six for the date and moon-phase display; nine for the day and twenty-four-hour display.

The 3940 was released in 1985, when Switzerland was in the throes of the quartz crisis, to 2006, when it was superseded by the ref. 5140, upsized by one millimetre, though in keeping with the 3940’s aesthetic.

In 2016, the 5940 was replaced by the 39-millimetre 5327, still persisting in the layout of its predecessors but featuring Breguet numerals for markers. The 5327 offers a more elaborate case, with scalloped edges, similar to those found on the Annual Calendar Chronograph ref. 5905.

As part of Patek Philippe’s Ladies’ First collection, the charming 7140 perpetual calendar in white or rose gold sits alongside the 4947 Annual Calendar and 7130 World Time. With a silvery sunburst dial housed in a 35-millimetre case, the 7140 also features a bezel set with 68 diamonds and a pin-type buckle set with 27 diamonds.

All Patek Philippe perpetual calendars are supplied as standard with an automatic watch-winder. Kept wound, they will not require adjustment until the year 2100.

Perpetual Calendar Chronographs

A Patek Philippe collection, or strictly speaking, a Patek Philippe collector cannot be complete without a perpetual calendar chronograph: alongside the world time, annual calendar, and Nautilus – and minute repeater – this is the high complication that thrust Patek into the role it plays and office it holds as Switzerland’s preeminent watchmaker.

The impetus to create a chronograph was driven by the company’s co-founder, Antoine Norbert de Patek, during his voyage to America in 1854. Patek, having observed the fecundity of the American economy as it emerged out of a downturn, frequently corresponded with Geneva, sharing of his experiences of this continent and their approach to timekeeping. In one such letter, Patek rheumatically (quite literally; a pain which accompanied his journey to the New World) declares, “Americans vociferously demand watches which are inexpensive, but they also demand that they are capable of calculating the speed of their trotting horses with split-second accuracy… they only know about Swiss cuckoo clocks.”

The watchmaker then commenced work on its first chronograph unveiled in 1856, a three-subdial pocketwatch which did not yet feature an automatic reset mechanism, but whose hand was returned to zero by a key. The template of this piece defined an aesthetic lineage for the chronographs that Patek was to release over the next two centuries.

The popularity of the chronograph over the following decades continued to be driven by the American market, who increasingly had a predilection to have the chronograph paired with other complications, the perpetual calendar, for instance. It will be familiar to most readers to read that names as historically significant as Henry Graves Jr. and James Ward Packard bankrolled some of Patek’s finest grand complications: the former with a 24-complication pocketwatch created in 1933, now known as the Graves Supercomplication; the latter, the first Patek watch with a celestial sky-chart among other chiming and calendrical complications.

With the increasing acceptance of wristwatches in the 1920’s, appropriated from a purely utilitarian purpose in the trenches of World War One to the fashion-pedestrian, Patek’s first split-seconds chronograph arrived in 1923, with its first chronograph, the reference 130, a year later.

The reference 130 was produced from the latter half of the ’20s till the end of the ’40’s, with a considerable number of dial variations; bicompax (two-counter) with both vertical and horizontal arrangements, notably also “sector” dials, which were an aesthetic contemporary to the era, derived from military and scientific applications. The term alludes to the divisions that isolate hours, minutes, and seconds into sectors.

The 130 was offered in various metals – white, pink, and yellow gold, pink gold and stainless steel, and stainless steel. The earlier, rarer 130s were offered as a monopusher chronograph, with start-stop-reset and time-setting performed via the crown, with the vertical bi-compax arrangement. These immensely rare monopusher 130s were equipped with Victorin-Piguet’s 13-ligne (one ligne is equivalent to 2.2558 millimetres) ébauche; later 130s from ’29 utilised the 13-130 movement from the Raymond Frerès company, now better known as Valjoux.

Offered in parallel to the 130 was its larger sibling – by close to four millimetres – the reference 530 (not to be confused with the Calatrava reference), introduced in 1937 and remaining one of the rarest chronograph references by the firm. Housing the Valjoux 23 and finished by Patek as the caliber 13-130, the 530 was offered in both pink and yellow gold, and highly rarely – in stainless steel during the ’40’s, of which fewer than ten have emerged at auction.

In the hand of the Stern brothers, who purchased Patek Philippe in 1932 during the Depression, Patek continued to uphold the popularity of the chronograph by pairing it with other complications, as seen here with the Ref. 1415, a unique world time chronograph that was produced in 1940, the forbear of the modern ref. 5930G of 2016.

We now reach a new period ushered in by the 1518 perpetual calendar chronograph.

Reference 1518 (1941-1954)

The antecedent, introduced by Patek during the Second World War. It utilises a Valjoux 13 movement, with the perpetual calendar module added by Victorin Piguet. A steel version (of which there are four) achieves a result in excess of 11million CHF at the Phillips: Geneva Watch Auction in November 2016. 35mm case. Famous wearers include the King of Romania, and Ed Sheeran.

281 watches produced; approximately 55 in rose gold, 4 in steel, rumoured 3 pieces in steel and rose gold. The remainder are in yellow gold.

Reference 2499 (1950-1985)

Interestingly introduced with a 4-year overlap to the 1518, the 2499 is considered by many to be the quintessential perpetual calendar chronograph, across four series with minor variations, including to the pushers, markers and numerals, as well as to the crystals. 37.5mm case, Valjoux 13 movement. Famous wearers include Eric Clapton, who wore a very rare 4th-series platinum version, of which it is thought that only two exist. A total of 349 pieces are created across the 35 years, most of which are in yellow gold. An estimated ten percent of production is executed in rose gold.

First Series, 1950 to mid ‘50’s – Arabic markers, tachymetric scale, rectangular pushers, leaf hands, acrylic crystal.

Second Series, ’55 to ’60’s – Arabic or baton markers, tachymetric scale, round pushers, dauphine hands, acrylic crystal. Some are double-stamped, retailed by Tiffany and Co.

Third Series, ’60 to ’78 – Baton markers, no tachymetric scale, round pushers, acrylic crystal.

Fourth Series, ’78 to ’86 – Similar to the third series, only offering a sapphire crystal. An example worn by Clapton achieves in excess of CHF3.4 million at Christies’ 2012 auction.

Reference 3970 (1985 – 2004)

Under the hand of Philippe Stern, the case size of the 2499’s replacement is reduced by 1.5mm down to 36 millimetres. Four series are produced; the watch introduces for the first time in a Patek Philippe, the highly-regarded Lemania 2310 manually-wound caliber, dating to 1942 and the product of a joint collaboration between Lemania and Omega, also found, in less refined form, in every Omega Speedmaster that went to space. Visually differentiable from the 2499 by the presence of a 24-hour indicator in the 9 o’clock subdial and a leap year indicator in the 3 o’clock subdial, the 24-hour indicator also served the function of enabling the wearer to avoid adjusting the calendar while the movement is meshed, engaged to change date (usually between 9pm to 3am).

First Series, 1986 – Featuring an opaline-silver dial with applied yellow gold baton markers and leaf hands and only offered in a yellow-gold case, the 3970 is fitted with a snap-on solid caseback that does not provide water resistance. The 3971, offered in parallel, is fitted with a snap-on display back that is also not water-resistant. The subdials complement but do not match the dial colour. Approximately 100 watches are made.

Second Series, ’86 – ’91 – Very similar to the first series, only with colour-matched subdials on the front and a screw-down caseback for improved water resistance. Watches with solid casebacks are designated 3970; with display casebacks, 3971. Also available with an integrated bracelet, doing away with the lugs, this radically different sub-model is designated 3970/002.

Third Series, ’91-’04 – Known as the 3970E, for “Etache”, “waterproof”, this series had watches supplied by default with both display and solid casebacks, which began a practice that persists until today. The idea for the latter was to permit the opportunity for engravings of family crests, or inscriptions, or one’s initials. More slender hands and longer baton markers with triangular tips complete the changes on the front.

Special Editions – offered in platinum, with Arabic numerals and the off-coloured subdials found in the first series. A custom, unique salmon-coloured version was produced for Eric Clapton. For the London Exhibition in 2015, a black-dial, “Breguet 12 Clapton dial” 3970 in rose gold was offered in conjunction with Patek’s 175th anniversary.

Reference 5020 (1993-1999)

Once considered an aesthetic oddball within Patek’s collection, the cushion-shaped ref. 5020 no longer meets with an ambivalent reception but is now a highly-collectible, rather rare, strong performer at auctions. Approximately 200 are estimated to be made, with approximately 20 in platinum, with diamond indices. 37mm. A platinum example sells for close to half a million USD at Sotheby’s “Important Watches” auction held in April 2018 in Hong Kong.

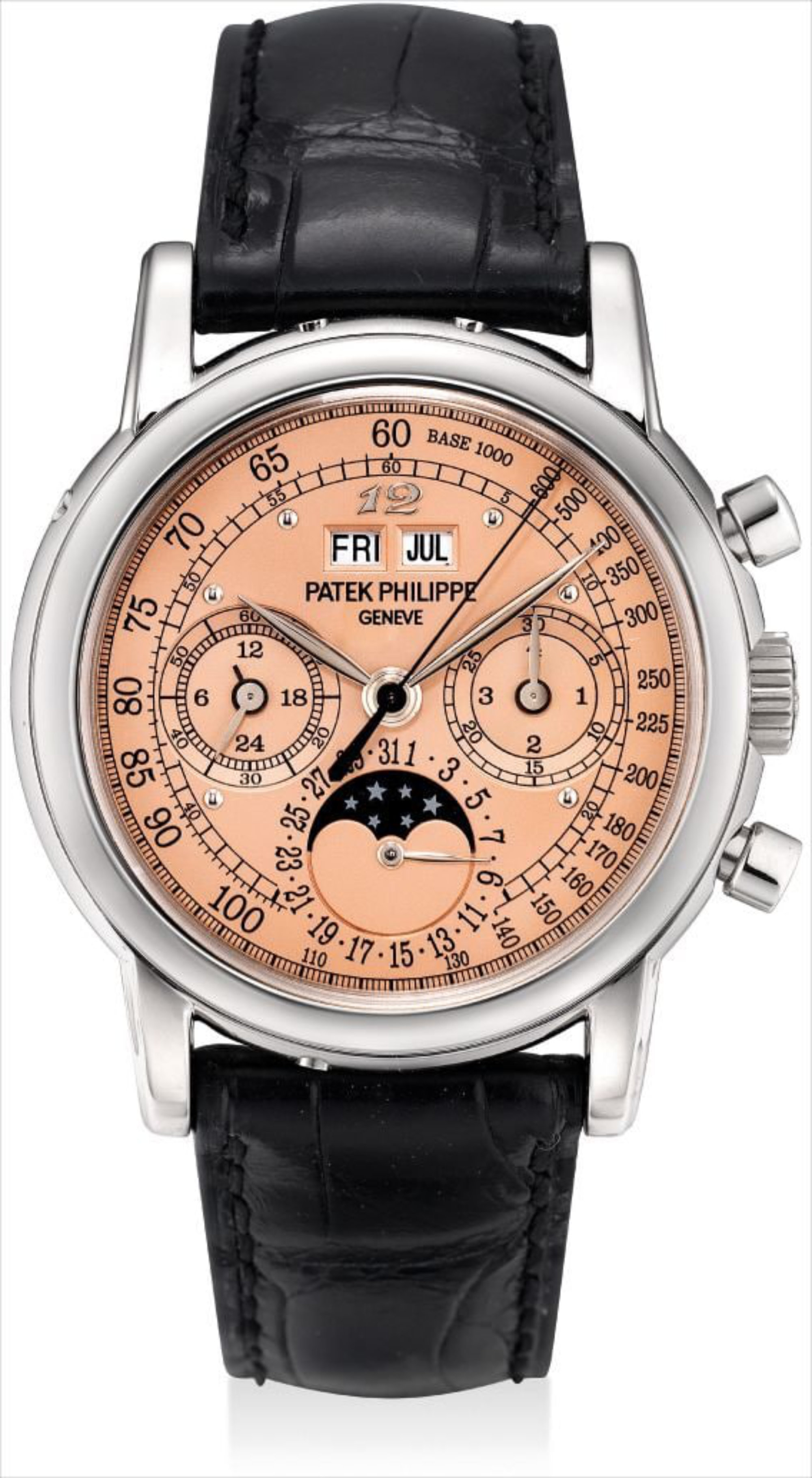

Reference 5970 (2004-2010)

Ah, the 5970. A watch with which I have a strong affinity and personal experience, and one that is consistently esteemed, if not considered a “grail” piece, by many collectors today. My own father prizes his 5970, with custom luminous hands (on account of his allegedly waning eyesight), even among the more complicated pieces in his collection – the rattrapante perpetual calendar and minute repeaters, for instance. Eric Clapton has had a set of four unique 5970s, replete with matching brick bracelets, made for him – since sold at auction for approximately double the market going for regular production 5970’s. John Mayer, the Grammy Award-winning guitarist, calls the 5970 “as good as it gets”. And one can see why: Thierry Stern, under whose hand the 5970 design and execution were overseen, was tasked with this coming-of-age project in 2001, when his father Philippe was president of the firm.

The product of his hand, which could be said was a stylistic bridge between his father’s generation and his own, was executed in a highly-nuanced, 39-millimetre case, housing the venerable Lemania 2310, optimised and refinished to Patek’s exacting standards. The dial, referencing the 3970 special editions produced for Mr. Clapton, accommodated the 3-subdial calendar display and moonphase, as well as a tachymetric scale that was bold enough to be easily legible, while constrained within the dimensions of the watch.

This was achieved by abbreviating the tachymeter scale, which lay within the (outermost) seconds track; the tachymetric scale disappears between the dates of the 13th and 19th. The rectangular pushers add the finishing touches to the 5970’s sporty, restrained aggressiveness. And those lugs! I must leave their description to those more bohemian than I.

The Lemania 2310 was the product of a joint collaboration between Lemania and Omega. Also found in the pre-1968 Speedmasters, as well as forming the blueprint for movements used by Vacheron Constantin, Audemars Piguet, Breguet, and others, Patek has extensively reworked the 2310 to the Geneva Seal (now Patek Philippe Seal) standards, not limited simply to finishing, but also to such minutiae as the mounting of the balance spring, the clutch profile, and the use of a solid blanking. It is quite common knowledge that Patek’s adaptation of the 2310 is the most smooth-winding of all the manufactures.

- 5970R (rose gold, 2004-2008); recent (Dec 2018, Sotheby’s) achieves USD120k at auction

- 5970G (white gold, 2004-2008); recent (Dec 2018, Phillips) double-sealed sells for USD160k at auction

- 5970J (yellow gold, 2008); sells for CHF112k at Phillips, Dec 2016

- 5970P (platinum, 2009-2010); sells for CHF188k at Phillips, Nov 2017

Reference 5270 (2011-present)

Patek’s first perpetual calendar chronograph to contain an in-house movement, the CH 29-535 PS Q. A laterally-coupled column wheel chronograph and the culmination of five years’ of development, the movement signified the end of close to two centuries’ worth of dependence on extrinsic movement manufacturers (Victorin Piguet, Valjoux, and Nouvelle Lémania), as had been the practice for even the greatest of marques. A more technical discussion of the CH 29 is covered under Complications: Chronographs. The 5270 has two apertures at 4:40 and 7:30, for the respective functions of displaying the leap year and indicating day/night. These indications were previously integrated into the subdials at three and nine o’clock, respectively. The 5270 has seen four dial (and bracelet/strap) modifications:

First Series – 2011, white gold, silver dial. Bereft of a tachymeter, unlike the 5970 that came before it, this maiden iteration of the 5270 has a clean, modern, monochromatic appearance.

Second Series – 2013, white gold, with choice of opaline silver or blue sunburst dial. The tachymeter makes a reappearance, but arguably without the refinement that characterised its forbears. In accommodating the radial calendar display, the tachymeter is visually depressed from approximately the 110 to 130 mark, an eccentricity that has since become known as “the chin”, in collectors-speak.

Third Series – 2015, white gold, opaline or blue Sunday dial. Tachymeter is now “integrated”, or superimposed, unto the calendar display; the track from 130 to 110 preferentially gives way to the calendar from the 13th to the 19th mark. This compromise echoes that made with the 5970 and some special variants of the 3970 and 5004.

Fourth Series – 2018, rose gold, on bracelet, and platinum, with respective black and golden opaline “salmon” dials. The former, while being very striking and weighty, is somewhat eclipsed by the rarity of the latter dial colour: Patek had only offered salmon dials in their most exclusive, if not unique pieces – Mr. Clapton’s one-off watches, for instance, as well as on the 5101P, a very special ten-day tourbillon. A very small quantity of salmon-dial 5970Gs were offered for the London Exhibition in 2015. On the 5270P, Arabic numerals make a comeback, not seen since the second-series 2499, adding another layer of intrigue to this watch.

Rattrapantes

This is one of the two complications about which I am most keen to discuss: the rattrapante (French; rattraper – to recover, recapture – the Germans say doppelchronograph) comes second in difficulty to design, finish, and assemble only to the minute repeater, and perhaps the primary reason as to why it is not on equal footing is owing to the fact that only physical tactility is a factor, not aural pleasure. It is considerably more complex to conceive and execute than a tourbillon, and a traditional column-wheel-operated split-seconds chronograph is considered by many to be close to the highest pinnacle of watchmaking prowess.

What is a split-seconds chronograph? A standard chronograph (Greek; khronographos – to chart time) tracks elapsed time for single events. A split-seconds chronograph is the unitary equivalent of two (or three) standard chronographs, in that it permits the timing of intermediate events; a horse race, for instance – one would want boththe overall elapsed time as well as the timings for each lap. How this is so –

- Activate the chronograph pusher (usually 2 o’clock); hands move in tandem.

- First event occurs. Press split-seconds pusher (usually in the crown) and record the time; one hand (the trotteuse; French, “second-hand”) stops, while the other continues running.

- Engage split-seconds pusher again; previously-stopped hand instantaneously catches up with running hand.

- Repeat as necessary.

Patek has had close to a century of watchmaking experience with the rattrapante wristwatch – strictly speaking, closer to a decade of in-house expertise, but that would perhaps be splitting hairs. The first split-second chronograph that Patek produced was not even assigned a reference number, merely No. 124.824; produced in 1923, this 33mm enamel-dialled beauty immediately recalls the much more familiar, and contemporary 5959 introduced in 2009.

The 5959 also shares a movement as fine and traditionally-constructed as this maiden rattrapante; immaculately finished, exquisitely delicate, the CHR 27-525PS was, at the time of its introduction in 2005, the thinnest split-seconds movement ever made. Owing to the immense difficulty of constructing, setting, and regulating this movement, Patek only produced about ten of the 5959 per year.

Another extremely special watch housing the same movement is the 5950A, now discontinued; these are some of the most intellectual, esoteric, exemplary complications ever made. Patek has not neglected the most discriminatory of female collectors: with the reference 7059, introduced in 2011 but since discontinued.

The 7059 essentially is a repurposed 5959, with a case size marginally larger to accommodate the diamond-set bezel; offered in rose gold and featuring 226 Top Wesselton diamonds, this is a watch in which the intellectual and the seductive are inextricably melded.

Prior to the 5370, which Patek introduced to great reception at Basel 2015, the last two-button (the aforementioned 5959, for instance, as well as the 5950, were monopusher split-seconds) chronograph offered was the 33mm Reference 1436, last manufactured close to half a century ago.

The 1436 was in essence a reference 130 with an additional split-seconds module; of the approximately 135 pieces made across thirty-three years, the majority were in yellow gold, with a few examples in pink gold, and three known in steel. One such example, made in 1941, achieved 2.8M CHF (without buyer’s premium) at the Phillips: Geneva Watch Auction Two in November 2015. The steel 1436 is more thoroughly covered in John Goldberger’s Patek Philippe Steel Watches, pg 302-305.

The presence of Reference 5370, introduced at the same Basel Fair as the somewhat-controversial ref. 5524 Calatrava Pilot’s Watch, would’ve assuaged nervous collectors who suspected Patek was becoming too pedestrian, too accommodating to global trends. Accommodating as it may be, Patek demonstrated with the 5370 that it is perfectly capable of producing a thoroughly modern watch – in wearability, aesthetic, size – but with a strong underlay of the traditional craftsmanship for which it is so highly regarded.

The presence of Reference 5370, introduced at the same Basel Fair as the somewhat-controversial ref. 5524 Calatrava Pilot’s Watch, would’ve assuaged nervous collectors who suspected Patek was becoming too pedestrian, too accommodating to global trends. Accommodating as it may be, Patek demonstrated with the 5370 that it is perfectly capable of producing a thoroughly modern watch – in wearability, aesthetic, size – but with a strong underlay of the traditional craftsmanship for which it is so highly regarded.

Featuring a svelte but complex 41-millimetre platinum case, a glossy, raven-black grand feu enamel dial (for which the enamel powder is repeatedly applied layer-by-layer, then fired) made by Cadrans Flückiger, itself owned by PP, and white gold Breguet-style numerals, the 5370 is proudly worn by the most discerning collectors. The luminous leaf hands give the watch an air of practical modernity, and the cabochons terminating the ends of the lugs are a wonderful feature paying homage to the design of its forbear, the 1436. The chronograph is activated and reset by ovalled rectangular pushers; the rattrapante by a co-axial button nested within the turbine-shaped crown. It is one of my favourite Patek Philippe watches.

Now about the 5004, 5204 and 5372

The first perpetual calendar wristwatch with a rattrapante chronograph by Patek was the venerable 5004, introduced in 1995, discontinued in 2011, with a purported limit of twelve pieces made per year, owing to the complexity of assembling and regulating the movement. That works out to approximately two hundred watches ever produced across four metals; Patek did release a limited edition of fifty in – get this – stainless steel as an “end of production” delight for the brand’s stalwarts, sold only from the Geneva PP Salon. The 5004, though not without its flaws, is an exceptional watch, and its strong performance at auctions is commensurate to the admiration it receives. Patek commissioned a one-off, unique titanium 5004T for the biennial Only Watch charity auction in 2013, benefitting the Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy charity – this single watch constituted close to two-thirds of the overall proceeds; approaching 3 million Euros.

The 5004 features the Lemania 2310 (in Patek speak, CH 27-70) chronograph movement with Patek’s proprietary split-second module and their perpetual calendar module, becoming the CHR 27-70Q. The resultant watch was weighty, though slightly stumpy with regard to mass distribution, sitting close to 15 millimetres thick while being a whiff less than 37 millimetres in diameter. There are quite many split-seconds chronographs around, but the good ones are few and far between: most experience “rattrapante drag” when activated. Rattrapante drag occurs in a typical, traditional set-up (as in the 5004) when the split-seconds wheel (which is attached to the chronograph wheel) is braked (that is, when it is paused) – resulting in undesired friction which translates to loss of balance amplitude and hence timekeeping accuracy.

With the 5004, Patek ameliorated this predisposition by implementing an isolator wheel, which was driven by a unidirectional “octopus wheel” : when the S-S function is activated, the isolator decouples the S-S wheel from the chronograph wheel. The all-new 5204, which replaced the 5004 in 2012, took this innovation further still: with a new isolator designed from the ground up, the isolator wheel spring is now part of the column-wheel cap, rather than sitting atop the split-seconds wheel, as it did on the 5004. This has the effect of reducing the overall height of the mechanism, making for a svelter watch. In addition, the isolator wheel is now bidirectional, improving reliability.

Part of what distinguishes the best rattrapantes from the merely “good” is alignment, regulation; most split-seconds chronographs have a thicker trotteuse seconds hand to cover for the imprecise alignment, or mating, of the two hands. Patek, in its quest for perfection, resolved this issue by redesigning the ruby roller: I will endeavour not to bore you with the details – take it from me that the ruby roller now has double flat-tipped edges that mate with the also double flat-tipped edge of the split-seconds lever, reducing the amount of play by a quoted 75%. The 5204 is a damn near perfect watch, and had I one, I would wear it as much as I could. It is also considerably more ergonomically balanced than its predecessor: at a 40mm diameter and 14.2mm high, in platinum or rose gold, it is hefty, yet supple and reassuring.

Inadequately appreciated, as rattrapantes tend to be (which to me, is an inadmissible oversight) – but very beautiful and fine, is the 5372P with which Patek beguiled the world in 2017; housing the incredible CHR 27-525 PS coupled with a perpetual calendar module, it introduced a new display aesthetic coupled with modern hues in a classical case (similar to that of the 5370P, only smaller), resulting in a compound of incredible allure. Incredible it almost is, for it is so inaccessible: I have never seen one in real life, and I have seen many Patek Philippe watches; I still yearn for that day, if for nothing else, simply just to say that I have seen a 5372.

Consider a Patek Philippe rattrapante – it is one of the very finest complicated watches one can acquire. You may interact with it, admire it, in a much more palpable manner than any of the other complications (rivalled only by the minute repeater).

Minute Repeaters

There are three complications for which Patek Philippe is arguably most renowned: the worldtime watch, the perpetual calendar chronograph, and the end-game grail – the minute repeater. The minute repeater, first completed by Patek in July of 1845, is the complication which one chases when the appeal of all the other pursuits, however elusive they once were, has been exhausted: the chronograph, the annual calendar, the perpetual calendar, the tourbillon wristwatch – in the words of Shakespeare, perhaps true of all collectors – “past reason hunted and, no sooner had, past reason hated.” There is no other complication, save perhaps to some rather lesser degree, the rattrapante chronograph, whose design, manual assembly, and iterative adjustment demands as much of a watchmaker’s prowess as that of the minute repeater; its acquisition, as much of a collector’s pockets, patience, and tenacity.

The analysis of any other complicated wristwatch is limited to the metrics of accuracy, tactile engagement, robustness, visual cohesion. But the nature of a chiming complication brings with it highly qualitative, yet often universally unanimous judgment on its aural aesthetics – a beautiful chime is a function of the quality of attack, harmony, pitch, volume, resonance, rhythm, and frequency.

To create a repeater that works reliably, much less one that sounds fabulous, is an ability limited to perhaps five or six maisons: as is true with any creative or technical endeavour, particularly at the top end, a tiny minority of watchmakers produce a disproportionate preponderance of minute repeaters worth their chime – this is not to suggest that there are, in absolute terms, many repeaters designed or produced in the first instance – the Pareto, or inverse-power-law distribution. Laurent Junod, long-time technical director at Patek Philippe, suggests that the number of watchmakers competent enough to make a repeater to be no more than fifty in Switzerland, of which fifteen of them work for Patek.

That Patek Philippe is at the apex of the minute-repeating hierarchy is recognised beyond dispute, as demonstrated by the extraordinary performances of the top bids Refs. 3939A, 5016A, and 5208T uniquely developed for the Only Watch charity auctions for Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy in 2011, 2015, and 2017 respectively; the 2014 sale of the “Graves Supercomplication” commissioned in 1925 by one of the foremost patrons of haute horlogerie, the New York banker Henry Graves, for CHF24 million, making it the most expensive watch ever sold to this day. Anecdotally – if you were to step into a room occupied by the most distinguished collectors and asked each “What modern watch do you aspire to own if barriers to entry were no consideration?”, the reply would overwhelmingly be “A Patek Philippe minute repeater”.

I was first acquainted with this complication as a fresh teenager, in Arthur Conan Doyle’s Sherlock Holmes: The Case of Lady Sannox. “The surgeon pressed the spring of his repeater and listened to the little tings which told him the hour. It was a quarter past nine. He calculated the distances, and the short time which it would take him to perform so trivial an operation…” It is precisely for this function that the repeater was designed: to tell time before the advent of Edison’s brilliance (or of Swan’s, Faraday’s, or Tesla’s, if one insists) with the electric light, and much later, with Madame Curie’s noble, if ultimately unfortunate, discovery of the phosphorescent properties of radium. For this reason minute repeaters were also adopted by the visually-impaired.

Ralph Teetor, prolific American inventor and engineer (most notably of the automotive cruise-control system) and acquaintance of fellow Patek Philippe patron, James Ward Packard, had in 1925 commissioned a platinum-and-gold cushion-cased repeating wristwatch. Teetor had been blind from the age of five from an accident in his workshop.

The repeater as a concept has become more palpable of late: I have had the quite recent privilege of handling, and listening to, the Refs 5539G and 5078R, with their respective white- and rose-gold cases. Owing to the plethora of contributing, and interacting, variables involved in determining the tone, volume, and tempo (the sub-factors of which are mentioned in paragraph two) of a particular repeater – the length, diameter of the gongs and their hardness, the case material, the physical relationship, fit, of the repeater movement relative to its case; these are but a few – it is impossible to decisively predict that a particular combination of materials and physical properties will produce an acoustic profile exactly matching that of a similar previously-cased, approved (by the ear of the PP’s president) repeater. It is because of this inherent unpredictability that only a maison like Patek Philippe can, with one foot firmly in order (in the Jungian sense) – complete mastery of the entire spectrum of watchmaking – afford to have the other in chaos, or the unknown.

The construction and optimisation of a Patek Philippe repeater is as follows: the gongs – usually circular, but analogous to a triangle in a classical orchestra – an alloy of hardened steel, with diameters ranging from .48 to .60 mm, are made by hand, one at a time, the amplitude of their vibration adjusted by the watchmaker iteratively filing away from their base; the pitch modified by filing away from the tips of the gongs. With the exception of the worldtime-minute repeating 5531R, whose gongs are attached to the case-band, the gongs are soldered to a boss, or base, which is then attached to the movement.

Patek makes 21 different grades each of standard (approximately one full circumferential length) and cathedral (approximately two full circumferential lengths) gongs; cathedral gongs, as found in the Refs. 5178, 5074, and 5304 et al, tend to produce very rich tones with particularly protracted reverberation. They are however, immensely challenging to manipulate: as cathedral gongs are only secured at one point, a helical arrangement of the gongs and recesses in the case are necessitated to preclude the gongs making contact with each other, or with the case, or the movement. There are two gongs; high- and low-pitched, therefore enabling three permutations of chimes – low, high-low, and high – for hours, quarters, and minutes. The fundamental parameters for Patek repeaters are an intensity of 60 decibels, and, for the longest possible strike – at 12:59 – chiming for 18 seconds.

The hammers, analogous to the metal ‘beater’ complementing the aforementioned triangle, possess an important relationship to the gongs: their mass, the force of their strike, as well as their recoil displacement, must be such that the volume is good, but not so great as to produce undesirable, extraneous noise. The rate at which the hammers hit the gongs is regulated by a centrifugal governor, silent in operation, unlike that of the low-pitched buzzing of the more traditional anchor governor. Excellent power expenditure and hence linearity in tempo is a trait of all Patek Philippe repeaters, not self-evident in other lesser repeaters; the rate of rotation of the (secondary) mainspring barrel is modulated such that the tempo does not perceptibly weaken during the striking of the final few minutes.

The centrifugal governor was first developed and perfected by Patek Philippe for the Calibre 89; fitted unto the last wheel of the governor train is a two-armed spindle – the arms of which are weighted at the ends and tensioned by minuscule springs – as the spindle rotates, there is a trade-off between the increased moment of inertia and angular acceleration, thereby regulating the rate of chiming; the (admittedly tired) analogue is a ballerina extending her arms to reduce her rate of rotation. Here the hammers are, in all their black-polished glory, displayed to full effect in the Ref. 5539G.

Perhaps most interesting is the choice of case material: yellow gold, rose gold, white gold, and platinum – these are currently offered in the standard catalogue; there is always the annual Only Watch charity auction to anticipate should one desire to acquire a unique steel- or titanium-cased Patek repeater. The case material which most collectors concur is likely to produce the most agreeable combination of volume, tone, reverberation, and overall warmth (a rich sound with low frequency) is rose gold, which for its relative predictability, is also the safest (so to speak), and hence the traditionalist choice for a first repeater. It is difficult to exactly delineate the nature of the sound a yellow or white gold case will produce relative to a rose gold case, owing to the many aforementioned confounding variables – even a gem-set bezel has an effect on sound transmission – though it is said that a white gold case yields a more crystalline, if harder tone, with higher-frequency, higher-amplitude peaks.

A platinum case is perhaps the most fascinating – one could think of the normal distribution of the acoustic qualities of Pt-repeaters as having high kurtosis, or heavy tails (a flatter distribution) – what this implies is that for every platinum repeater which has a muted, slightly austere tone, with a relatively narrower range of frequencies (owing to the density of the metal) – there is another with the potential to be exceptionally exquisite, distinct to that of any gold case; sonorous, loud, rich, crystalline, without being harsh. White, rose, or yellow gold is very likely to produce an excellent chime – as would be expected of any Patek Philippe minute repeater – but should one possess the ability to acquire multiple repeaters, a platinum case may well be a worthy option. My suggested order of acquisition would be: 5074R, 5539G, 5178G, 5208P. One has to submit an application through your Authorised Dealer to acquire a Patek Philippe minute repeater; justification would involve your motivation for acquisition, philosophy for collecting in general, and your comprehension and past patronage of this Genevan house. Mr Thierry Stern makes the final decision.

The process for a Patek Philippe minute repeater to pass muster is such: the single watchmaker who works on the repeater from beginning to end – typically 200 to 300 hours of assembly, excluding further optimisation – approves it by him-, or herself; it then proceeds to a anechoic, echo-free chamber, where the parameters of its chimes are recorded and computationally analysed against the template of previously approved and archived repeaters, ensuring continuity in the acoustic qualities across all Patek chiming watches. The repeater is then presented to the head watchmaker overseeing the chiming complications, and then finally – and most famously – to Thierry Stern, President, for his approval; in the same way as it was presented to the ear of his father and grandfather before him. The great majority of repeaters are approved by this stage, though not to the extent where it is a mere formality.

Donald de Carle writes in his seminal Complicated Watches and their Repair, “We have all heard the phrase, cool, calm and collected, and it can be applied to meet many occasions, but it has a real personal significance to to the person undertaking the care of repeaters…it is for the student to make himself proficient, by acquiring through practice, the mentality necessary to do the work now to be discussed.”

I went to an omakase dinner with a dear friend recently; there is some continuity between the uncompromising excellence of a hardened itamae and that of a watchmaker who single-handedly creates a minute repeater. Stoic in demeanour, intensely invested in perfection – their work a reminder that these heights are attained with decades of single-minded commitment to one complex task. With such multi-sensory experiences a virtuoso can afford to push the bounds of the known only when he, or she, has mastered the rules; the resultant product revivifying one’s existing notions of human achievement. Born of purpose, persisting in dispensability, chosen for fascination – the beauty of the minute-repeater a microcosm of the philosophy of fine watchmaking and collecting in toto.

The Alarm Travel Time

As instinctively outré (at first reception) as it is mechanically impressive, the ref. 5520P, introduced at Baselworld 2019 is quite a sight to behold: a quartet of crowns emanating from both sides of the watch. But a closer study reveals this watch to be a quite unique, unprecedented development of complications: a watch that offers the same time-tracking utility as the Calatrava Pilot’s Travel Time, with the addition of an alarm mechanism. Now, you may think, is not an alarm complication what one acquires as a – shall we say, more accessible – complication than the other chiming alternatives? A typical alarm timepiece does not chime, even; it buzzes, the product of energy liberated from a separate mainspring, driving a hammer which hits a metal membrane-plate, perforated to enable better sound transmission.

So how did Patek exalt the mechanical alarm to the plane of a high complication? Borrowing from its expertise in minute repeaters and chiming watches, like a traditional, pedestrian alarm, the new AL 30-660 S C FUS movement also uses a separate mainspring, but the commonality ends there.

This movement utilises a circumferential gong, and it employs a silent centrifugal governor that regulates the hammer striking the gong, all mechanical attributes that characterise a Patek Philippe minute repeater. The alarm is mechanically dependent on the local time display; the chiming lasts up to forty seconds, at a frequency of 2.5Hz (that is, 2.5 strikes per second). The movement is finished to the highest possible standards, with a medley of black-polished caps, a magnificent Calatrava cross atop the governor, internal angles, and generous, convex bevels.

Four design patents have been filed for this movement; one of which permits the setting of the alarm to one-minute accuracy to the next quarter hour (for instance, setting at 11:59 am/pm for 12:00 am/pm). Others pertain to the alarm display; the alarm logic functions, and the protective mechanisms that disable inadvertent user interference to mechanically damage the movement. The user may switch to another time zone during the alarm activation without any risk of damage; deactivation occurs when a mechanical “finger” linked to the strikework barrel detects that the barrel is not fully wound.

Aside from these technical accomplishments, the 5520P also offers significant merits of functionality: it is the first Patek Philippe chiming watch to feature a water-resistant case, certainly a useful requisite for a traveller’s timekeeper. It remains to be seen if Patek will offer future minute repeaters in water-resistant cases. The 5520P does not displace the significance of minute repeaters in Patek Philippe’s legacy, and neither is it eclipsed by it; it is a demonstration that this family-owned firm will continue to push the envelope to make exceptional watches.

[Editors Note: In the lead-up to the 2019 Patek Philippe Watch Art Grand Exhibition David wrote a series of articles covering the gamut of watches Patek Philippe makes, including: Part 1 The Calatrava, Part 2 Patek Philippe Rare Handcrafts, Part 3 The Patek Philippe Nautilus, Part 4 The Patek Philippe Aquanaut, Part 5 The Patek Philippe Complications, Part 6 The Patek Philippe Grand Complications and Part 7 Astronomical Exceptionalism]